Coccid Thorn Gall on Emory Oak - Olliffiella cristicola

Fascinating and bizzare "Witch Hat" galls in Southern Arizona

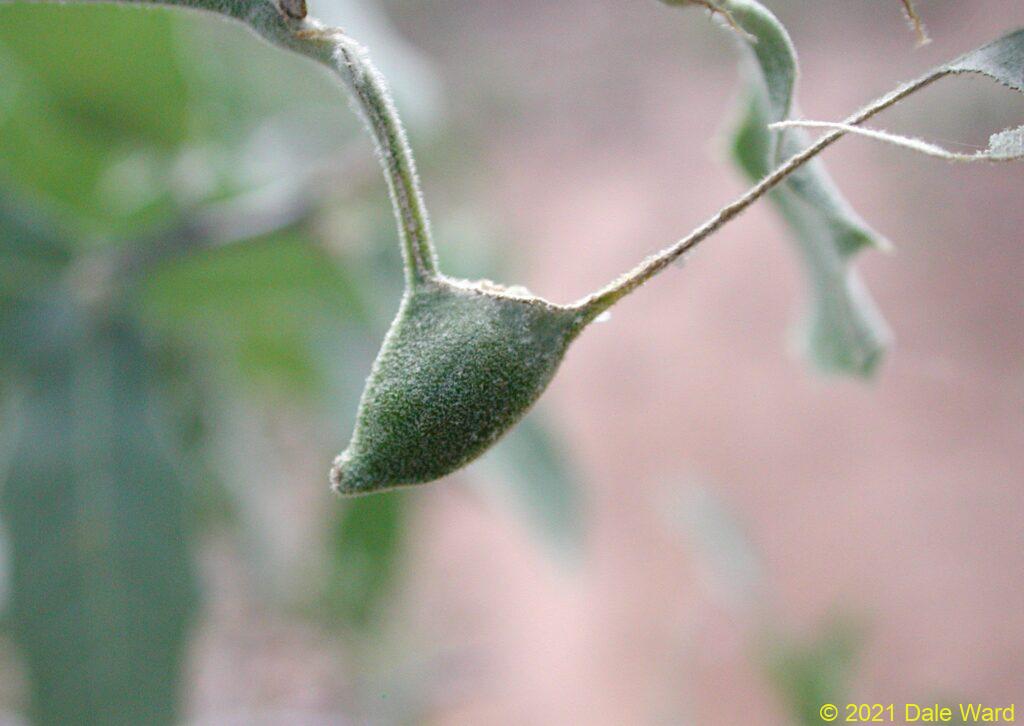

View of a gall, on ventral surface of oak leaf

View of a gall, on ventral surface of oak leaf

In September of 2002, I was walking along a trail in Gardner Canyon, in Arizona’s Santa Rita Mountains. I noticed a 4-5’ high shrub on the side of the trail. It looked like some type of scrub oak, or Emory Oak. What was unusual, though was the shrub’s leaves - about half of the leaves had a prominent cone resembling a witch’s hat projecting from the ventral side.

Those “witch hats” were galls, growths of plant tissue that is often caused by insects. Wasps, flies, aphids or other insects “trick” the plant into making a house for the insect to live inside. The insect tells the plant to build it a home, then the insect lives in the home - often while it is feeding upon the plant! Plant galls seem exotic and improbable, they are surprisingly common. In the photo below, you can see a large round object near the “witch’s hat” galls, that looks like an unripe orange. That round object is yet another type of gall that this oak tree is infected with, one that I suspect was caused by a Cynipid wasp.

But what were the witch’s hats?

A view of at least four “Thorn Galls” on an Emory Oak, along with a billiard-ball-sized round gall from another species. I suspect the round gall is from a Cynipid wasp.

A view of at least four “Thorn Galls” on an Emory Oak, along with a billiard-ball-sized round gall from another species. I suspect the round gall is from a Cynipid wasp.

The witch’s hat galls were growing from the center vein of the leaf, and projecting down. On the upper (dorsal) side of the leaf above each gall, there was a slit. The slit was surrounded by brittle, brown, leaf tissue. I suspect that was this brittle tissue formed a roof over the hollow interior of the gall. Then there was a lighter green band of tissue surrounding the slit, that was the same color as the oak leaf’s veins. I suspect was the wall of the gall, as seen from above. If that were true, then the witch’s hats had thick walls surrounding hollow chambers.

Entrance to the gall chamber, on the dorsal surface of the oak leaf. The brown area marks the boundaries of the interior gall chamber, the light green indicates the thickness of the walls around the gall chamber.

Entrance to the gall chamber, on the dorsal surface of the oak leaf. The brown area marks the boundaries of the interior gall chamber, the light green indicates the thickness of the walls around the gall chamber.

A very interesting thing - the galls were very attractive to ants.The ants would crawl over the surface of the leaf, and enter the gall through the slit. The ants were Dolichoderines, I think that they were Dorymyrmex insanus.

_Dorymyrmex_ _insanus_ ants at the entrance to the gall chamber. In addition to the two ants at the entrance, there is at least one ant inside the gall chamber.

_Dorymyrmex_ _insanus_ ants at the entrance to the gall chamber. In addition to the two ants at the entrance, there is at least one ant inside the gall chamber.

A _Dorymyrmex_ _insanus_ ant explores the leaf-top opening of the gall.

A _Dorymyrmex_ _insanus_ ant explores the leaf-top opening of the gall.

Some of the ants would enter the galls through the slits, and some would just put their heads into the slits. I suspect that the ants inside the gall were passing food to the outside ants via trophyllaxis.

_Dorymyrmex_ _insanus_ putting her head into the gall chamber. The ants outside the gall would antennate the ants that were already inside. I’m not sure if the ants inside were passing honeydew out via trophyllaxis, or if the outside ant was checking to see if there was room to enter.

_Dorymyrmex_ _insanus_ putting her head into the gall chamber. The ants outside the gall would antennate the ants that were already inside. I’m not sure if the ants inside were passing honeydew out via trophyllaxis, or if the outside ant was checking to see if there was room to enter.

A _Dorymyrmex_ _insanus_ ant explores the leaf-top opening of the gall.

A _Dorymyrmex_ _insanus_ ant explores the leaf-top opening of the gall.

Some of the galls were on leaves that had been almost entirely eaten, presumably by caterpillars. All that was left of the leaves were the leaf veins - and the gall.

Some herbivore, such as a caterpillar, had eaten some of the leaves on the tree. They would leave at least the central leaf vein, sometimes a few of the lateral veins. In this case, the caterpillar also left the Thorn-gall on the leaf’s mid-vein.

Some herbivore, such as a caterpillar, had eaten some of the leaves on the tree. They would leave at least the central leaf vein, sometimes a few of the lateral veins. In this case, the caterpillar also left the Thorn-gall on the leaf’s mid-vein.

These “left behind” galls were still attractive to the ants.

I think the “left-behind” gall probably still had a coccid inside of it because the gall was still attractive to _Dorymyrmex_ _insanus_.

I think the “left-behind” gall probably still had a coccid inside of it because the gall was still attractive to _Dorymyrmex_ _insanus_.

I was very curious about the brown tissue surrounding the gall slits. The ants would chew at the tissue with their mandibles, worrying the tissue until it broke off. That would enlarge the slits.

In the photo below, you can see an ant carrying away a small fragment of the dry, brown tissue. In the foreground of the photo, you can see other fragments of the dry tissue which had presumably been removed earlier. It looks as though the ants were actively enlarging the slits by chewing away the brittle brown tissue.

_Dorymyrmex_ _insanus_ ant carrying fragment of the brown tissue that surrounds the gall opening. The ants were picking at the gall opening, perhaps trying to widen it. You can see other brown crumbs of the opening’s tissue in the lower third of this photo.

_Dorymyrmex_ _insanus_ ant carrying fragment of the brown tissue that surrounds the gall opening. The ants were picking at the gall opening, perhaps trying to widen it. You can see other brown crumbs of the opening’s tissue in the lower third of this photo.

Red arrows showing fragments of the gall opening.

Red arrows showing fragments of the gall opening.

I really wanted to find out what was inside these galls, and what the ants were doing. I collected one of the galls.

Side view of galled oak leaf with my hand for scale, showing how the gall projects below the leaf.

Side view of galled oak leaf with my hand for scale, showing how the gall projects below the leaf.

Dorsal view of galled leaf in my hand, for scale. Showing entrance into the gall chamber.

Dorsal view of galled leaf in my hand, for scale. Showing entrance into the gall chamber.

I used my pocket knife to carefully section the gall that I’d collected. The walls of the gall were made by successive layers of tissue. Down at the bottom of the gall, near the point of the “witch’s hat”, there was a round creature that looked a bit like a button. The underside of the creature was orange, and its upper side was a deep reddish orange.

There was a droplet of clear fluid on the creature. That droplet of fluid was probably “honeydew” - sugary solution that the creature made by feeding on the sap of its host plant.

This little critter was a Coccid - a type of Scale Insect. They are related to Aphids. I had no idea that they formed galls.

I cut into one of the galls. You can see the reddish-orange gall-inducing insect, a Coccid, nestled into the bottom of the gall. There’s also a drop of honeydew on the top of the coccid.

I cut into one of the galls. You can see the reddish-orange gall-inducing insect, a Coccid, nestled into the bottom of the gall. There’s also a drop of honeydew on the top of the coccid.

Section of gall, showing coccid, with arrow pointing to droplet of honeydew.

Section of gall, showing coccid, with arrow pointing to droplet of honeydew.

So far, I thought that this whole situation was pretty pretty interesting. But then it got really fascinating.

While I was taking photos of the sectioned gall, I put the gall on the ground. In a very short time, probably less than a minute, a Dorymyrmex insanus ant found the Coccid and began to feed on the excreted honeydew on the Coccid’s back.

Than another ant came over, and another, and…

The speed with which they discovered the Coccid, and the number of ants that came over, suggests to me is that the ants might be able to sense the Coccid from a distance, that there was something that had attracted the ants.

The fact that the ants went straight to the droplet, with very little searching or fumbling around, suggests to me that the attractive odor was coming from the fluid itself, not the walls of the gall or the body of the Coccid.

After I cut the gall open, I put the gall onto the ground so that I could photograph it. Within a minute, a _Dorymyrex insanus_ ant came over to the gall and began drinking the honeydew. This particular ant had probably been drinking at another gall prior to this - note how fluid-distended her gaster is already, like a waterballoon. More _Dorymyrmex_ appeared and also began drinking within another minute or so.

After I cut the gall open, I put the gall onto the ground so that I could photograph it. Within a minute, a _Dorymyrex insanus_ ant came over to the gall and began drinking the honeydew. This particular ant had probably been drinking at another gall prior to this - note how fluid-distended her gaster is already, like a waterballoon. More _Dorymyrmex_ appeared and also began drinking within another minute or so.

The honeydew is primarily comprised of sweet plant sap. Since ants don’t typically come running to the smell of an injured oak petiole with its sap, I wonder if the the Coccid was releasing a pheromone in the honeydew that attracted the ants.

If that’s the case, then I suspect that the Coccids were essentially calling the ants into their gall chambers.

When I got home, I took more photos of the gall and the Coccid in the lab. In some galls, the insect convinces the plant to build special cells lining the walls of the gall that secrete nutrients to the insect. I couldn’t see for-sure evidence of that, but the gall had dried out quite a bit. I think the inner-most white layers in the gall were wax fibers secreted by the Coccid.

Ventral surface of Coccid (right of photo), base of sectioned gall (left of photo).

Ventral surface of Coccid (right of photo), base of sectioned gall (left of photo).

Close up of bottom (“the pointy end”) of the sectioned gall. This is where the Coccid was nestled. You can see that the wall of the gall is comprised of layers of plant tissue. That white, innermost layer _might_ have been nutritive tissue, but I couldn’t tell for sure. I suspect, though, that it was wax fibers secreted by the Coccid.

Close up of bottom (“the pointy end”) of the sectioned gall. This is where the Coccid was nestled. You can see that the wall of the gall is comprised of layers of plant tissue. That white, innermost layer _might_ have been nutritive tissue, but I couldn’t tell for sure. I suspect, though, that it was wax fibers secreted by the Coccid.

I spent quite some time trying to figure out what this insect was, beyond calling it “a Coccid”. That is like saying a Mockingbird is “a bird”…true, as far as it goes, but you’re losing a lot of information.

Then, recently, I acquired a copy of Ronald Russo’s (2021) marvelous book “Plant Galls of the Western United States”. At last, there was my insect and its gall.

He calls the gall a “Thorn-gall”, and the Coccid is the “Thorn-gall Coccid” (Olliffiella cristicola). They are locally common on Emory Oaks in Arizona and New Mexico.

They are the only known Coccid in North America that induces galls. How cool is that?

I’ve been thinking more about the slit opening on the top surface of the leaves, and how attracted to the Coccid the ants were. Some gall-forming insects rely on ants to remove the waste honeydew from inside the gall, so the insect doesn’t drown in sap.

But…if that were the case…wouldn’t the ants have been tending the Coccid inside its gall throughout its life? Given how the ants were chewing and worrying at the brown tissue at the gall entrance, I would have thought that the ants would have long ago broken that tissue away. Since the ants were actively enlarging the slits while I watched, I suspect that the ants had not been working at the slits for all that long a time.

I wonder if the Coccid turns that extreme ant-attractiveness off and on as it needs it.

So, for example, maybe the Coccid needed that slit opening created, or opened more broadly at that point in its life cycle. Maybe to let the Coccid’s “crawler” offspring out?

Or maybe so the ants could carry its offspring away, to be “farmed” by the ants?

Seems as though the more one looks at the world, the more questions arise.

Sources:

Russo, Ronald A. 2021. Plant Galls of the Western United States (Princeton Field Guides, 142). Princeton University Press. ISBN-10: 0691205760.