Colorado Blackfly Larvae

Looking at Blackfly larvae in a mountain stream in southwestern Colorado

Blackfly larvae on a rock, with fast, shallow water flowing over them.

Blackfly larvae on a rock, with fast, shallow water flowing over them.

We’ve been having an extended heatwave over the last couple of weeks (mid-June 2021), so I decided to head up to a creek in the San Juan Mountains to cool off.

The creek was beautiful, flowing with clear, cold water. I sat on a rock near the creek and reveled in the cool air and the sound of the running water.

I also noticed that some of the rocks in the stream were covered with something that looked like velvet. I’d seen this before, in New Hampshire - these were Blackfly larvae.

The Blackfly larvae attach themselves to rocks by spinning a silken pad that sticks to the rocks. Then the larvae hold on to the pads using little hooks on the end of their abdomens. The larvae’s heads are then free to wave in the water current.

Blackfly larvae on a rock, with fast water sweeping over them.

Blackfly larvae on a rock, with fast water sweeping over them.

The larvae have a pair of mouth parts that have evolved into fan-shaped nets. They spread these nets out in the water current and use the nets as filters, gathering and eating passing bacteria, algae and other bits of organic material. Since they are anchored to the rock at their tail end, the larvae’s bodies and head wave sinuously in the current. They are quite beautiful.

Blackfly larvae on rocks, with fast, shallow water flowing over them.

Blackfly larvae on rocks, with fast, shallow water flowing over them.

Since the water in the creek was low, and the rocks that the larvae were on was covered with less than a half-inch of water in some places. I decided to try photographing the larvae through that thin layer of water. The downside to that approach is that the resolution of these photos is not great. The upside is that I really liked the way the water looked as it ran over the rocks.

Looking at Blackfly larvae in the fast, shallow waters of the creek.

Looking at Blackfly larvae in the fast, shallow waters of the creek.

Photographing through the water also meant that I didn’t disturb the larvae. When they are disturbed, they contract into a near-ball shape - say “so long” to their graceful, sinuous movements. I was able to get (admittedly blurry) photos of them with their mouth-part “nets” extended as they filtered the water.

Cropped view of Blackfly larvae on a stone. Some of the larvae have their feeding combs extended.

Cropped view of Blackfly larvae on a stone. Some of the larvae have their feeding combs extended.

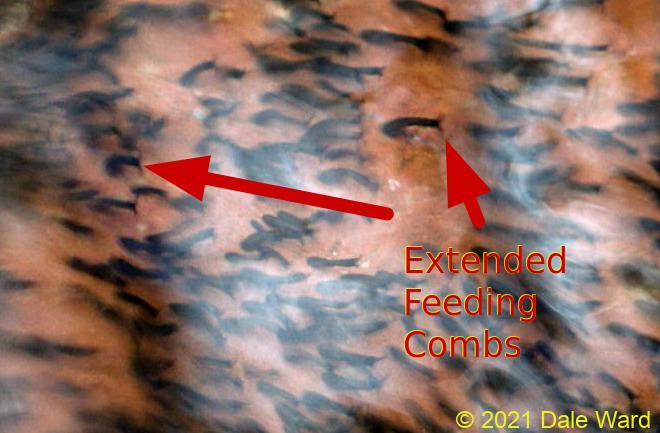

Same as previous photo - but with arrows indicating the feeding combs of a couple of larvae.

Same as previous photo - but with arrows indicating the feeding combs of a couple of larvae.

Blackfly larvae on rocks, with my finger for scale.

Blackfly larvae on rocks, with my finger for scale.

Closer view of Blackfly larvae on rocks, with my finger for scale. They larvae are attached to the rocks by their hind ends. Their heads are waving free in the current. They have ‘feeding combs’ on their head that they extend when my finger isn’t poking at them. The current sweeps food particles into these feeding combs.

Closer view of Blackfly larvae on rocks, with my finger for scale. They larvae are attached to the rocks by their hind ends. Their heads are waving free in the current. They have ‘feeding combs’ on their head that they extend when my finger isn’t poking at them. The current sweeps food particles into these feeding combs.

On one rock, which had just the merest skin of water on it, I found what I think is a Blackfly adult emerging from its pupa.

Blackfly adult emerging from a cocoon (center of photo) in shallow water. You can also see a Stonefly larvae in the upper-left quadrant of the photo. The Stonefly eventually came over and examined the emerging fly, but did not bother it further.

Blackfly adult emerging from a cocoon (center of photo) in shallow water. You can also see a Stonefly larvae in the upper-left quadrant of the photo. The Stonefly eventually came over and examined the emerging fly, but did not bother it further.

I wonder if this Blackfly was ahead of the other larvae developmentally because it was in such very shallow water. Perhaps the larvae can sense when the water level is dropping, and hasten their development in the same manner that Tiger Salamander larvae ‘know’ to metamorphose into adults as their pond dries?