Tadpole Shrimp and the Timing of the Rains

Visiting one of my temporary Tiger Salamander pools in the Southwestern Desert, thinking about how the timing of the rains may affect which their biotic composition.

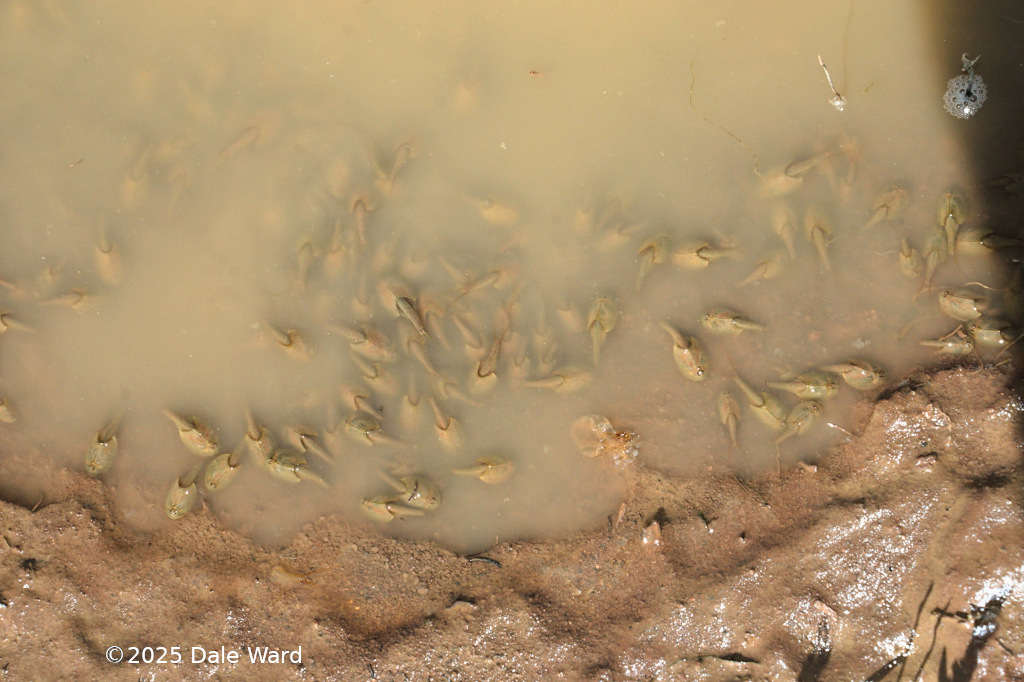

Group of Tadpole Shrimp in the shallows of a drying desert pool.

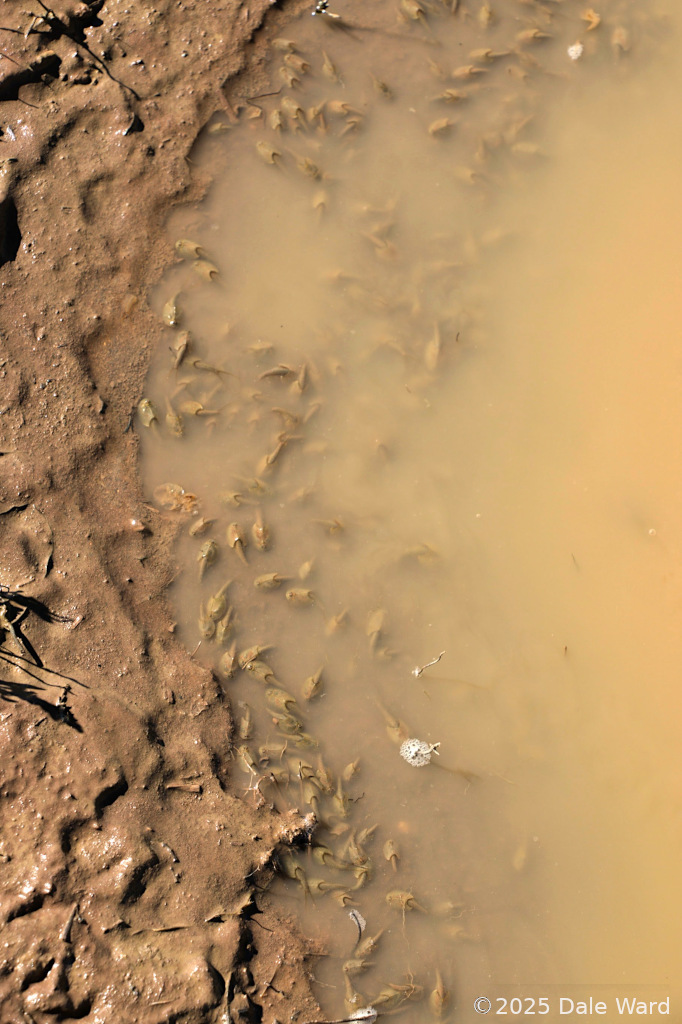

Group of Tadpole Shrimp in the shallows of a drying desert pool.

Three or four days after my first visit to one of my favorite ephemeral pools in Canyons of the Ancients, I drove out and visited it again. I was eager to see how much water was left in the pool, and how the Tadpole Shrimp (Triops longicautatus) and Spadefoot Toad tadpoles were doing.

The pool had shrunk substantially, and was only a couple of inches deep even in its deepest parts. The Tadpole Shrimp were noticeably larger - I’d guess that the average size was almost twice as large as on my previous visit. That is an astonishing rate of growth.

The Tadpole Shrimp seemed especially numerous around the edges of the pool. I was quite pleased about this, as I was able to get some really neat photos of them in the shallows.

Group of Tadpole Shrimp in the shallows of a drying desert pool.

Group of Tadpole Shrimp in the shallows of a drying desert pool.

The shrinking pool, the shallow water and the density of the Shrimp made me think of photos I’ve seen of drying waterholes in Africa, densely packed with Hippos and Crocodiles.

The airfare to see these Tadpole Shrimp was substantially less, though.

Group of Tadpole Shrimp in the shallows of a drying desert pool. The shrimp were all stirring up big clouds of mud as they try to feed.

Group of Tadpole Shrimp in the shallows of a drying desert pool. The shrimp were all stirring up big clouds of mud as they try to feed.

Group of Tadpole Shrimp in the shallows of a drying desert pool.

Group of Tadpole Shrimp in the shallows of a drying desert pool.

Away from the edges of the pool, I could see some of the Tadpole Shrimp swimming in the marginally deeper water. They would often be swimming upside down, just under the surface. My assumption is that they were skimming filtering out zooplankton and algae that were using the underside of the water surface as a substrate. Or perhaps the Tadpole Shrimp were searching for insects that would get caught in the water film?

The Tadpole Shrimp, when they were swimming upside down, showed up as bright red against the muddy water. I suspect that’s because of haemoglobin - the Shrimp have gill filaments at the base of some of their legs.

In deeper portions of the pool (2-3”), Tadpole Shrimp would flip upside-down and skim along the water surface and feed. Their legs were moving so quickly that they were a blur.

In deeper portions of the pool (2-3”), Tadpole Shrimp would flip upside-down and skim along the water surface and feed. Their legs were moving so quickly that they were a blur.

I could also see something that showed up as bright white on the underside of the Tadpole Shrimp heads. I had no idea what that was - were they carrying something? So I scooped one out with my hand.

Close-up of the underside of a Tadpole Shrimp. The white portions of their exoskeletons were very noticeable when they swam upside-down at the surface of the water. Just above my thumb, you can see rows of legs with gills attached.

Close-up of the underside of a Tadpole Shrimp. The white portions of their exoskeletons were very noticeable when they swam upside-down at the surface of the water. Just above my thumb, you can see rows of legs with gills attached.

The bright white area on the underside of their heads was just the color of their exoskeleton, the Shrimp were not carrying anything. I’ve got no idea why these portions of the Shrimp are white while much of the rest of the carapace is pigmented.

Closeup of Tadpole Shrimp. They were quite densely aggregated, often the tail of one Shrimp would be laying across the carapace of another.

Closeup of Tadpole Shrimp. They were quite densely aggregated, often the tail of one Shrimp would be laying across the carapace of another.

Tadpole Shrimp in the shallows of drying desert pool.

Tadpole Shrimp in the shallows of drying desert pool.

In some places the Tadpole Shrimp forced themselves into water so shallow that they were resting on wet mud, with their eyes poking up out of the mud, like Crocodile eyes.

I ended up crawling around on my hands and knees around the edges of the pool, trying to get photos from different angles. It was quite a bit of fun.

Tadpole Shrimp foraging in the shallows of an ephemeral desert pool.

Tadpole Shrimp foraging in the shallows of an ephemeral desert pool.

Tadpole Shrimp in a drying desert pool.

Tadpole Shrimp in a drying desert pool.

I could see the separate facets of the compound eyes. They remind me of the eyes on Trilobite fossils.

The genus name of this Tadpole Shrimp is “Triops”, meaning “Three Eyed”. In a lot of these photos, you get pretty good views of the eyes of the Tadpole Shrimp. There are two large eyes, which are compound eyes. Each of these eyes is comprised of a number of single photo-receptive units called “ommatidia”. These compound eyes are raised above the level of the shrimp’s head, sort of like a Crocodile’s eyes are raised.

The Tadpole Shrimp’s third eye is between the two compound eyes. It’s a “naupliar ocellus”, and is comprised of a single ommatidium. It is not raised up above the exoskeleton, as the compound eyes are. That ‘third eye’ like a window into the Shrimps head, I guess.

Tadpole Shrimp in a drying pool. You can clearly see where the genus name of ‘Triops’ comes from: “Three-Eyed”.

Tadpole Shrimp in a drying pool. You can clearly see where the genus name of ‘Triops’ comes from: “Three-Eyed”.

I spent an hour so photographing at this pool before I decided to hike into the canyon and visit another pool - one that usually has Tiger Salamanders in it.

I think the Tiger Salamanders in this area breed primarily in the Springtime, using water from the Winter rains and the snow melt. The pool I was going to visit had been dry through the Springtime this year, though - so there had been no Tiger Salamanders earlier in the year.

With the good late Summer monsoon rains this year, I thought this pool would have water in it now. Would there be Tiger Salamander larvae?

This is the pool that sometimes has Tiger Salamander larvae and no Tadpole Shrimp. This year, it was dry in the Springtime when the Salamanders breed. Now, the pool has filled in the Summer monsoons and it has Tadpole Shrimp (and Spadefoot Tadpoles) but I saw no Tiger Salamander larvae.

This is the pool that sometimes has Tiger Salamander larvae and no Tadpole Shrimp. This year, it was dry in the Springtime when the Salamanders breed. Now, the pool has filled in the Summer monsoons and it has Tadpole Shrimp (and Spadefoot Tadpoles) but I saw no Tiger Salamander larvae.

No, there were no Tiger Salamander larvae - but lots of Spadefoot Toad tadpoles, and lots of Tadpole Shrimp.

Huh. That’s interesting. Years when there have been Tiger Salamander larvae in the pool, I didn’t see any Tadpole Shrimp there. This year, when the pool was dry in the Spring, I didn’t see any Tiger Salamander larvae, but saw lots of Tadpole Shrimp.

Tadpole Shrimp tend to hatch out during the Summer Monsoons. I’m guessing that if they hatch out in year with a wet Spring, when there would be Tiger Salamanders in the pool, the Tadpole Shrimp would get quickly eaten.

I wonder if the Tadpole Shrimp rely on the very ephemeral pools to keep them away from predators such as the Tiger Salamander larvae, in the same way that Tiger Salamander larvae seem to use ephemeral waters to keep themselves away from predatory fish.

Very cool, if that’s the case.

Tadpole Shrimp and Clam Shrimp in a photo aquarium

Tadpole Shrimp and Clam Shrimp in a photo aquarium

I’ve thought a lot about why I am so fascinated by the Tadpole Shrimp.

There is the obvious reason - the fact that they are aquatic animals that live in a desert, which gives a literal “dust to dust” nature to their life cycles. And it’s true, I am fascinated by this aspect.

I’m also fascinated by the way they move.

When they are swimming in open water, you can’t really see their little swimmerette legs busily pushing them. So they just seem to magically zip along. This no-appararent-means-of-propulsion, in combination with the Shrimp’s overall shape, always makes me think of the Cylon Raiders in the new Battlestar Gallactica series.

And when they are in shallow water, the Shrimp move with a strange, sudden jerkiness that seems preternatural. I had a similar sensation when I was a kid and watched that old Jason and the Argonauts movie. There’s a part of the film where a group of skeletons come to life via stop-motion photography. Back then, we weren’t used to seeing special effects in those days, and those skeletons were just astonishing to me and my friends. I get that same feeling of amazement when I watch the Shrimp.

But I think what I like about them the most is that the Shrimp seem so improbable. They are so active, so frantically alive, yet when you pick one up in your hand, theres’s not a lot of flesh there, certainly not enough to support that amount of life.

They seem like totems, like fetishes, that have been animated. As if somebody gathered twigs, cactus spines, and leaves into bundles, then muttered an incantation and wove their hands around in secret ways. And then, magically, the twig bundles came to frantic life.

That’s the feeling I get when I’m watching the Tadpole Shrimp - that I’m seeing something truly magical.

I’m not sure if any of the above will make sense. But I love watching them.

Sources:

Wikipedia’s Triops longicaudatus page was very useful - much of the information here came from that page.

Animal Diversity Web’s Triops longicaudatus page. They did a really nice job on their entry for these critters.