Tumbleweed Shield Lichen

I first saw these strange organisms on a patch of bare rock next to a trail at the Carpenter Natural Area in Cortez, CO. They were obviously Lichens, but they weren’t attached to the ground. They were scattered in loose…

Tumbleweed Shield Lichen. Tumbleweed Lichens are not fixed to the ground, they are moved through the world by the wind and the rain

Tumbleweed Shield Lichen. Tumbleweed Lichens are not fixed to the ground, they are moved through the world by the wind and the rain

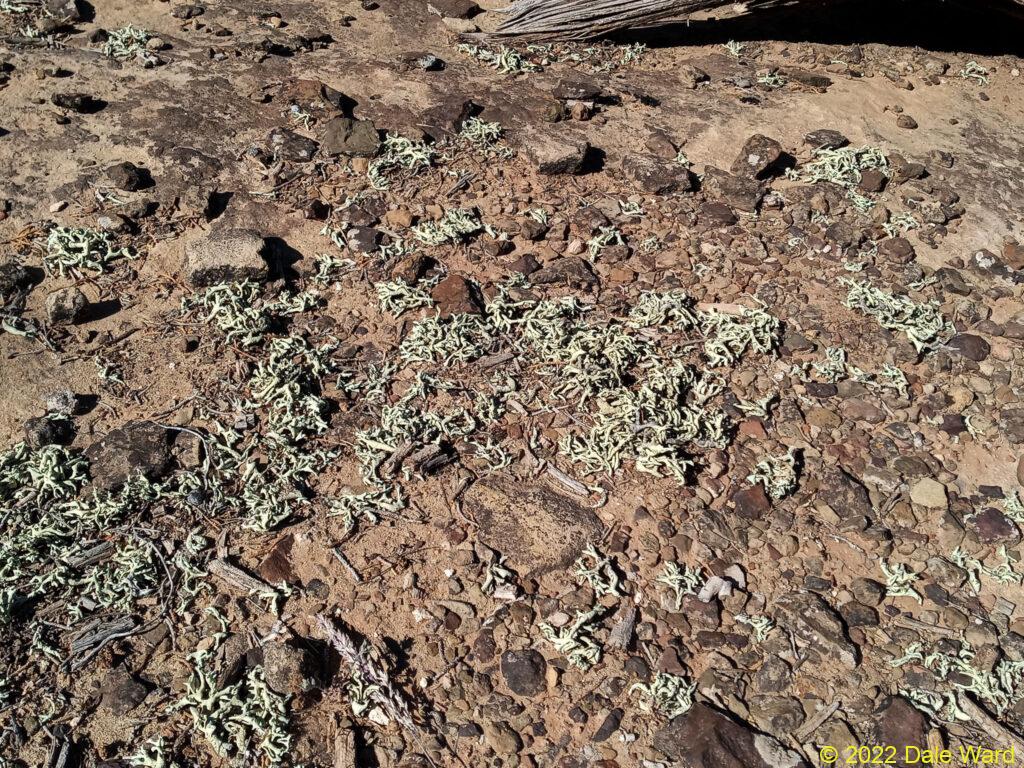

I first saw these strange organisms on a patch of bare rock next to a trail at the Carpenter Natural Area in Cortez, CO. They were obviously Lichens, but they weren’t attached to the ground. They were scattered in loose clumps on the broken rocks.

They strangely reminded me of the clumps of dried-up Seaweed that you might find on a beach at the high-tide line, the way they were clustered. What on Earth were these?

Fortunately, the Carpenter Natural Area folks had posted an identifying sign near them. These were Tumbleweed Shield Lichens.

Scattering of Tumbleweed Shield Lichen on bare rock. The Lichens were not _attached_ to the rock. Although the Lichens were dry, their appearance reminded me of clumps of Seaweed washed up at a high-tide line on a beach.

Scattering of Tumbleweed Shield Lichen on bare rock. The Lichens were not _attached_ to the rock. Although the Lichens were dry, their appearance reminded me of clumps of Seaweed washed up at a high-tide line on a beach.

These things are fascinating. They are not attached to the ground, so they blow and roll with wind and the water, like seaweed on a shoreline. Do they gather together in these spots in the same way that flotsam collects in eddies of water? I’ve seen single plants of these organisms on rocky slopes, away from other Tumbleweed Lichens. I wonder if those Lichens will eventually be blown or swept into groups like this.

Vanessa Diaz’s Masters Thesis on the Xanthoparmelia Lichens of Colorado recognizes 18 species of Xanthoparmelia in Colorado, but only four species “vagrant” species. She uses the term “vagrant” to mean that they don’t attach themselves to a substrate, and they reproduce asexually by physical fragmentation. That seems strange to me, I had first assumed that one of the advantages of them being blown into groups like this was that it made reproduction easier for them.

Regarding identification of these Lichens to species, Vanessa Diaz says:

In the field, Xanthoparmelia can be particularly difficult to identify to species. When comparing literature, descriptions and keys generated over the course of history of this genus, it is clear that many are relatively morphologically indistinct…

…prior to the present writing, existing Xanthoparmelia keys were not straightforward and often unreliable…

She recommends using various chemical spot tests, and sometimes Thin Layer Chromatography, for identification.

Being a fundamentally lazy person, I used photographs and the range maps to support a my very tentative ID of these as Xanthoparmelia chlorochoa or Xanthoparmelia vagans.

Close-up of Tumbleweed Shield Lichen. Gosh this stuff looks like dried up Seaweed.

Close-up of Tumbleweed Shield Lichen. Gosh this stuff looks like dried up Seaweed.

The reason I care about identifying these Tumbleweed Shield Lichen to species is that I came across some interesting articles while I was researching these Lichens.

Come to find out, these Lichens had been implicated in strange livestock poisonings over the years. There had been anecdotal reports of cattle and sheep Lichen poisonings from the 1930s.

Tumbleweed Shield Lichen on bare rock, with hand for scale.

Tumbleweed Shield Lichen on bare rock, with hand for scale.

And then in Wyoming, in 2004, observers found 400-500 free-ranging Elk weakened and paralyzed, laying down on their chests. They were “…alert and responsive, but unable to rise.” The Elk eventually died or were euthanized. The Elk had signs of myopathy, but it was unknown if the myopathy was caused by a toxin, or was exertional.

The Elk also voided red urine, which would be consistent with an exertional myopathy…but there was no detectable hemoglobin or myoglobin in the urine.

They found Tumbleweed Lichen in the rumen of at least some of the Elk. And when they fed the Tumbleweed Lichen to captive Elk, they saw similar symptoms.

Tumbleweed Shield Lichen on rock with moss. This photo is after we had had a period of rain - the Lichens and Moss are relatively swollen with water.

Tumbleweed Shield Lichen on rock with moss. This photo is after we had had a period of rain - the Lichens and Moss are relatively swollen with water.

After the Elk poisonings, laboratory researchers tested Tumbleweed Lichen in domestic sheep. They found that the Sheep found the Lichen to be quite palatable, happily munching down a diet of 100% Lichen.

After a couple of days, most of the Sheep developed coordinational and muscular issues - weakness, stiffness, etc.

And all of the Sheep voided bright red urine, which had no detectable myoglobin or hemoglobin content.

The researchers felt that the coordinational problems of the Sheep were of muscular, rather than neuronal origins, - but couldn’t find consistent signs of muscle damage in histopathology.

This is probably my ignorance speaking, but I not sure how a neurological examination could differentiate between a muscular problem and a problem at the motor end plate of the neuron. I wonder if perhaps the mode of action of the toxin is that it interferes with neuronal transmission of signals to the muscle?

The authors think that since the red urine contains neither myoglobin nor hemoglobin, its red coloration is likely caused by secondary metabolites of the Lichen.

They mention that Xanthoparmelia chlorochroa is used by Navajo weavers as a red or orange dye for wool, and wonder if some of the same secondary metabolites cause the red urine.

This is a very strange world.

Sources:

The Wikipedia Xanthoparmelia chlorochroa entry

Cook, Walter Elliot, Merl F. Raisbeck, Todd E. Cornish. 2007. Paresis and Death in Elk (Cervus elaphus) due to Lichen intoxication in Wyoming. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 43(3): 498-503. August 2007.

Dailey, Rebecca N., Donald L. Montgomery, James T. Ingram, Roger Siemion, Merl F. Raisbeck. 2008. Experimental reproduction of tumbleweed shield lichen (Xanthoparmelia chlorochroa) poisoning in a domestic sheep model. J Vet Diagn Invest 20:760-765.

Díaz, Vanessa Marie. 2016. The Xanthoparmelia of Colorado: Diversity and Distributions. MS Thesis for the University of Colorado Department of Museum and Field Studies.